Proposing a Decision Support System for Scouting Talent and Weighing Competing Objectives

Photo by Ailura on Wikimedia Commons.

Photo by Ailura on Wikimedia Commons.As part of a semester-long assignment for my graduate studies, I’ve been working with a group of fellow students to envision and construct a prototype decision support system (DSS). Still in development, our DSS intends to pair professional soccer players' event-level data with multi-criteria decision analysis methods—resulting in a system which “assists clubs with the identification, scouting, and acquisition of world-class talent,” as we state in our initial proposal.

Even just building out a small-scale version of this, I’ve come to learn, is an incredibly tall task.

The Data Component and Model Design

In order to power our system with a sample of real players' demographic information and event- and match-level statistics, I turned to the series of JSON files powering Wyscout’s platform. Our system will be primarily targeted at clubs with mid-sized budgets from the top leagues in the world, so I decided our sample of players should accurately reflect the environments in which their typical low-risk, high-reward prospects are found.

Thus, I limited our search to the (10) European countries whose top-level competitions are just below the level of the top leagues in the world, according to UEFA country coefficients: Russia, Portugal, Belgium, Ukraine, Turkey, Netherlands, Austria, Greece, Denmark, and Switzerland ( = 28 competitions). From there, I identified the players currently contracted with the clubs competing in those 28 leagues (as of February 17, 2019; = 11,458 players). And lastly, I retrieved match-level statistics for each player, dating back to the 2015–16 season ( = 486,789 cumulative matches played).

While other attributes are sure to be considered by scouts and other decision makers, the efficacy of our model hinges on two key components: talent maximization (in the short-, medium-, or long-term) and cost minimization.

As for the latter piece, for now, we’re relying solely on the market value provided for each player in the data set, derived from Transfermarkt’s model. (It’s worth noting that actual transfer values often do not reflect these ones, for any number of explicable or inexplicable reasons.)

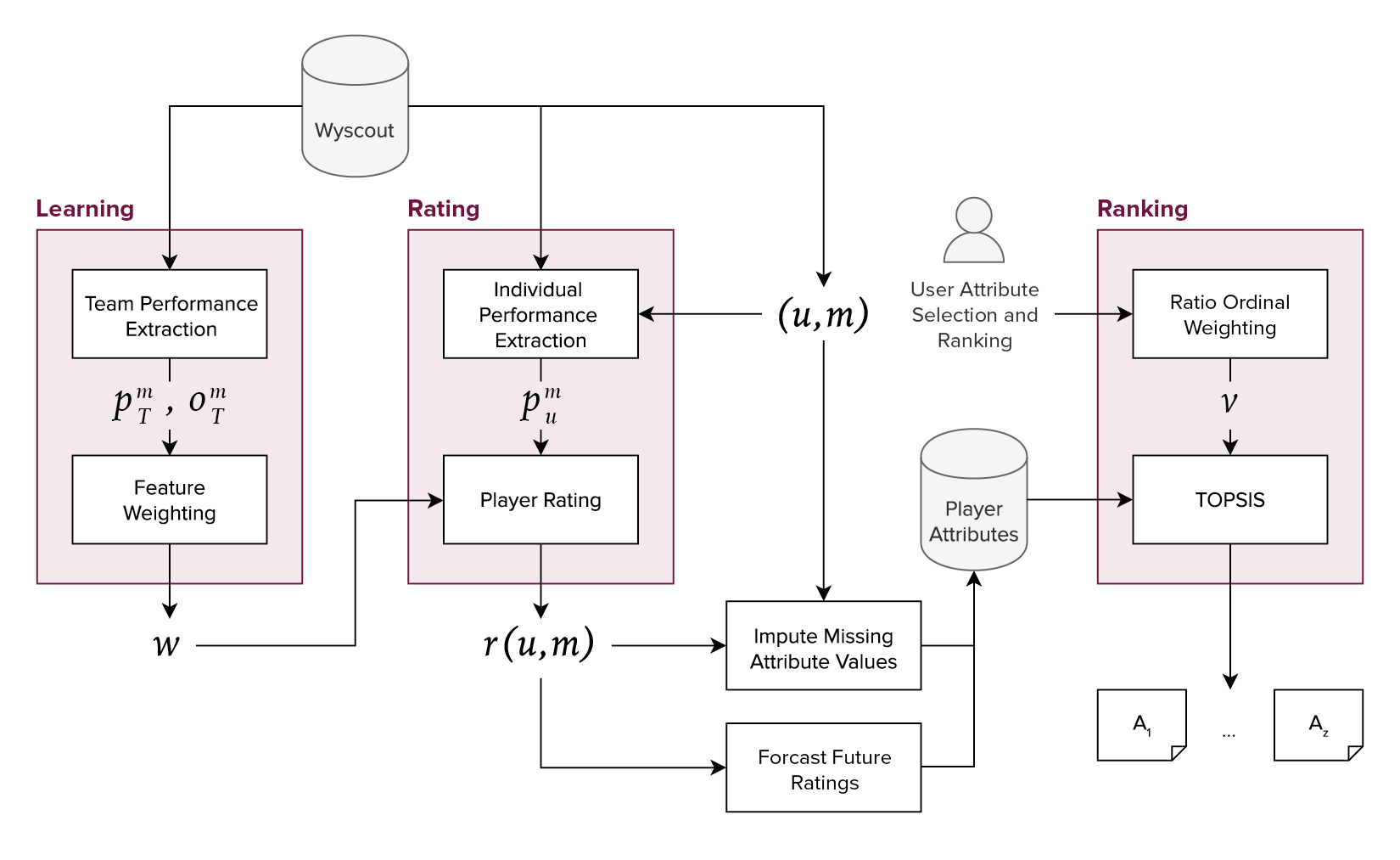

Whether we deliver a viable proof of concept, then, falls heavily on our ability to quantify players' skill level in the most objective manner possible. Our approach, which I’ll touch on in greater detail in the next section, is sketched out in left-hand side of the model diagram below:

Adapted from an analysis carried out by Italian researchers, our process for developing current skill ratings for each player in our data set is as follows:

Aggregate players' event-level data, , to the match level, , for each team,

Assign a binary outcome variable to each tuple, where resembles a win for the corresponding team and resembles a draw or loss for the corresponding team

On that matrix, train a classification model, such as linear support vector machines (LSVM), and extract the coefficients for each type of action

Apply those coefficients as feature weights to the matrix containing each players' () event-level data, , for each match,

The result, , is used to determine a player’s current skill level, after undergoing the following transformations:

- Using Bayesian statistics, relative competition strength is determined and weighted into each rating value

- Each performance is normalized by the number of minutes played

- For smoothing purposes, the value used by the decision model will be a rolling average of some to-be-determined timeframe (e.g., 5 or 10 weeks)

Overall, the logic behind this approach checks out. Ultimately, a player’s inherent value lies in the degree to which he or she improves the team’s likelihood of winning any given match. So, it makes sense to first determine which types of actions help or hinder the team, and then to evaluate a player’s performance based on those findings.

In practice, however, applying that logic proved to be far more difficult than it had seemed.

Training the Classification Model

At first, I pulled match-level data from nearly 5,000 unique games—yielding nearly 10,000 observations—across the 28 competitions for the 2018/19 season. As best I could, I attempted to replicate the model constructed by the Italian researchers, given the variables I had available. After several futile hours, however, all I had was a dozen or more classification models, all of which predicted the same outcome for every observation.

As such, I was forced examine two key differences between my approach and theirs. The first was obvious, yet manageable. Their set of inputs were far more granular and had higher dimensionality; I could solve for that by aggregating the player-level data—which contains 300+ types of actions—up to the match level.

The second, I believe, is a structural flaw in their approach. In their research, they explicitly lay out a sound argument for the exclusion of goals as features: The difference in the number of goals scored singularly determines the outcome of any given match. Why, then, were assists not also excluded? Goals don’t always come with assists, but assists are inherently tied to goals.

This, I felt, boosted their model performance, and that assertion was evident in their results. The top seven positively weighted features were all of the seven types of assists used as inputs.

With a new set of training data, and with that added knowledge of our performance benchmark for the model, I found much greater success in my next attempt. In the feature selection process, one additional piece of insight I gathered from the previous, unsuccessful attempts was to include only on-the-ball actions.

As you may well imagine, this makes it particularly difficult to evaluate defensive abilities—a gripe with event-level data I’ve shared in past. In this particular context, including defensive actions such as blocks and clearances in the model tends to backfire for defensive players. This is because, at the match level, a greater number of these types of events typically means that a team is under siege, and thus that they are more likely to lose the match, yielding a negative coefficient. When applying that coefficient to a player’s performance, it dramatically decreases the ratings of players actively involved in thwarting opponents' attacks, which runs counter to how their overall performance impacts the outcome of the match. Defenders typically don’t have much impact on whether they are placed in those types of situations, and conversely, much of their most impactful play happens off the ball—closing down valuable spaces on the field.

I acknowledge, however, that the role of modern fullbacks and center backs is continually evolving. In this era, a greater share of the responsibility is placed on them to contribute to offensive actions—igniting the start of an attacking move and generally positioning themselves higher up the pitch. And for those reasons, the model may well capture enough of what today’s scouts are seeking in emerging talents who will fill those positions.

The new training set consisted of more than 5,000 observations of 45 input variables each, and the new LSVM model was tuned using 10-fold cross validation and a cost parameter of 1. Its performance was considerably better than previous efforts (0.71 AUC and 74% accuracy), and the resulting coefficients more closely resembled a perceived reality. Actions which most negatively impacted a match’s outcome included red cards, yellow cards, and losses in dangerous areas of the player’s own half, while some of the actions with the greatest positive values included shots from dangerous areas, opportunity creations, and actions during a counter attacking sequence.

Content with those results, I weighted each player’s performance using the coefficients, resulting in their raw score for each match.

Weighting by Competition Strength

One of a scout’s greatest challenges must be projecting how a player’s performance will translate across leagues and/or national boundaries. As a result, this was another key consideration in constructing our model.

Recently, I’ve seen an analysis such as this conducted by Ben Torvaney for OptaPro’s 2018 Analytics Forum, and the same approach would have transferred well to our application. However, given some functional constraints—namely, time and computational power—we determined that it would be beyond the scope of our assignment to carry out an analysis to such an extent. That is, while our data set was large enough to have a considerable number of players transferring among different leagues, our approach would need to produce a similar outcome, while not holding constant the performance of each individual player, nor differences in age.

Instead, for the domestic competitions for which there was enough data, I calculated each player’s average performance rating, standardized per 96 minutes on the field (the average length of the matches in our data set), and excluded instances of those who played fewer than 10 matches (i.e., 960 minutes) in each competition. Using a single competition as an index, I applied the Bayesian estimation supersedes the t-test (BEST) model to determine the expected difference of means between each pair of competitions. The outputs of this model informed the competition weights later applied to each raw player performance rating.

Once again, the results of this analysis mostly held up against a perceived reality. My index, the Russian Premier League, was weaker in strength than Italy’s Serie A, the German Bundesliga, and the top divisions in both Argentina and Brazil, while it was far greater in strength than all of the regional and developmental leagues included in the data set.

Player Positions and Versatility

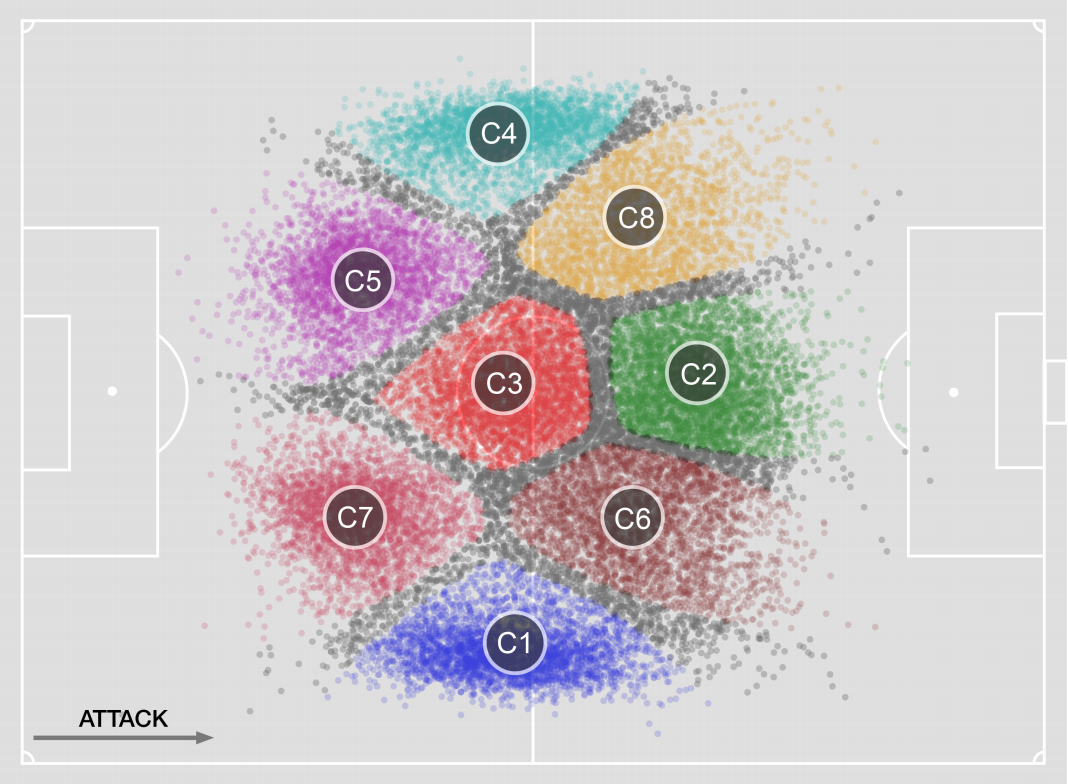

In their analysis, the Italian researchers clustered outfield players into eight different position types, based on the locations of their on-the-ball actions. A depiction of the resulting clusters is below.

We determined that these clusters will inform the position variable applied to our final decision model. However, given that Wyscout’s data already includes positional information for each match and player, itself informed by cluster analysis, there was no demonstrated need to draw our own positional clusters.

Though we’ve yet to apply it, another key attribute of the Italian researchers' findings is the concept of versatility. In short, by evaluating how well and/or consistently a given player performs when assigned to different types of positions, we could feasibly quantify how versatile he or she is—often a sought-after trait, particularly for younger players.

Future Considerations

Our next major task will be using the weighted performance values, derived using the steps above, to project the future skill levels of young talents. In a perfect world, we would have a data set of players robust enough to establish projections similarly to the approach taken by Dutch company SciSports. They are able to use a clustering algorithm to associate young players with established players who exhibited similar traits when they were of a similar age. An average trajectory, therefore, of that set of established players is used to quantify the young players' likely progression and ceiling.

However, given that we have not developed such a robust data set for our prototype, we’ll likely apply a forecasting model to serve the same purpose. One major wrinkle, for which we’ve yet to come up with a solution, is sufficiently accounting for gaps in performances caused by 1) injuries or 2) off-seasons.

Once our projections are established, that will put us in a strong position to deliver a prototype DSS which accurately weighs all factors, as defined by the user. Again, the efficacy of our model hinges on two key components: talent maximization (in the short-, medium-, or long-term) and cost minimization. By default, these two features will already be the top two when the user is prompted to rank-order the factors which matter most to them. (The user will also be prompted to state whether they are building for the present or future with each transfer, which will adjust the emphasis that the decision model places on current versus future skill levels.)

In order to generate the set of feature weights for the decision model, the ratio ordinal method will be applied, with the decision maker’s ranked-order selections serving as the inputs. The resulting weights will inform the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) model and help generate the final output: a ranked-order list of optimal transfer targets. The TOPSIS model is based on the assumption that, “the optimal alternative should have the shortest distance from the ideal solution and the farthest distance from the negative-ideal solution.” It was selected for its ability to both maximize benefit and minimize cost criteria.

Top-Performing Players, As Things Stand

Taking into account only each player’s current skill level—based on performances between July 1, 2018 and February 17, 2019, weighted by competition strength, standardized by minutes played, and segmented by the positional clusters referenced above—below are the top performers who are currently contracted with clubs in one of the 10 aforementioned countries:

Left-sided Attacker

- O. Sparre Klitten, AaB U19

- A. Erokhin, Zenit

- J. Okkels, Silkeborg

- G. Masouras, Olympiakos Piraeus

- Rafa Silva, Benfica

Central Forward

- P. Onuachu, Midtjylland

- L. de Jong, PSV

- S. Kulish, Dnipro-1

- A. Razborov, Irtysh

- I. de Camargo, Mechelen

Right-sided Attacker

- O. Tkachuk, Oleksandria U21

- E. Smyrnyi, Dynamo Kyiv U21

- Marcos Junior, UD Oliveirense

- R. van Wolfswinkel, Basel

- Z. Aboukhlal, PSV II

Left-sided Midfielder/Fullback

- T. Damgaard, Vejle U19

- J. Christjansen, Lyngby

- X. Schlager, Salzburg

- D. Mironov, Leningradets

- R. van der Venne, Go Ahead Eagles

Central Midfielder

- Alejandro Pozuelo, Genk

- K. Aliev, Khimki

- Taison, Shakhtar Donetsk

- I. Kogut, Dnipro-1

- N. Holm Pedersen, Silkeborg U17

Right-sided Midfielder/Fullback

- D. de Wit, Ajax

- V. Grubeck, FC Juniors OÖ

- A. Grünwald, Austria Wien

- J. Ekkelenkamp, Ajax II

- K. Vermeulen, RKC Waalwijk

Left-sided Central Defender

- A. Plotnikov, Zenit St. Petersburg II

- M. Shorkin, Torpedo Moskva

- S. Reese, Horsens

- V. Demin, Ufa II

- Ü. Kurt, Boluspor

Right-sided Central Defender

- D. Chistyakov, Tambov

- M. Goropevšek, Volyn

- E. Mbende, Cambuur

- E. Dudikov, Sokol Saratov

- N. Havenaar, Wil

Seeing the inclusion of names such as that of PSV forward Luuk de Jong and recent Toronto FC debutant Alejandro Pozuelo is reassuring, and seeing a smattering of reserve and academy players is intriguing. It is either the case that these players are wildly outperforming their peers and the competition weights aren’t sensitive enough to these outliers, or that they are actually ready to make the jump up to top-tier play.

Closing Thoughts

In no particular order, here are some parting thoughts on the topic:

From a scouting perspective, it is near impossible to boil down a player’s performance to a single metric—especially if that metric only takes into account event-level data. Even just going through those motions on a relatively small sample of data proved to be immensely difficult.

Given that the volume of on-the-ball defensive actions has a negative correlation with match outcomes, this would not be an optimal method for evaluating defensive abilities. Incorporating some other method, as well as some tracking data, would be necessary.

As performance data becomes more readily integrated into the day-to-day operations of clubs, one or more of the leading providers of scouting data should consider adding a decision support system to their suite of products. As with any other type of DSS, the need for internal culture shifts and system buy-in will represent the largest obstacles. But considering just how vast the talent pool is, I could foresee a well-built, enterprise-level tool such as this having abundant positive impacts on the efficiency and potency of scouting departments.

Data: Wyscout