Four Ways U.S. Soccer's Youth Task Force Can Make a Difference

Photo by Nik Shuliahin on Unsplash.

Photo by Nik Shuliahin on Unsplash.With the 2026 FIFA World Cup bid in the rearview mirror, U.S. Soccer President Carlos Cordeiro now has his eyes set on an arguably taller task: opening the ranks of the youth game to those previously shut out.

Speaking before U.S. Youth Soccer’s annual general meeting last month, the newly-elected president’s talking points on the matter matched the ones from the campaign trail. “The landscape is too fragmented and fractured,” Cordeiro started. He also bemoaned an overemphasis on winning and the “high cost of ‘pay-to-play.'”

In search of solutions, Cordeiro’s pitch to the crowd was a modest one: a task force to assess “how we can do better.” If and when that task force comes to be, here are some ways it can start forging pathways.

Create a centralized system for information-sharing.

You can’t solve a problem you haven’t adequately defined. This may sound obvious, but know that, at this very moment, the sport’s leaders don’t even have a definitive headcount of their active participants. By extension, they couldn’t possibly know which players are there, nor which are missing.

The task force’s first priority must be to answer those questions. And to answer those questions, they’ll need to work with member associations to develop a centralized and consistent method of collecting, storing, and analyzing this information.

This could be a win-win for all parties. Cordeiro signaled toward strained relationships between the associations and the federation: “Some asked whether it still made sense to be a member of the Federation or whether the fees you pay are reasonable.” Developing a centralized system for information-sharing rights that ship, and it makes the day-to-day duties of administrators that much easier.

Downstream, the benefits may continue to pile up. If sophisticated enough, such a system also has the potential to make scouting and talent identification more efficient. From the perspective of the athlete or parent, it could help them identify and carve out the most optimal pathway forward.

Most importantly, however, it’s a step toward clearly defining the problem—ensuring that all members of the task force start from the same place of understanding.

Identify the areas with the greatest need.

U.S. Youth Soccer CEO Christopher Moore last year admitted, “Knowing who your members are [is] the first step in being able to meet their needs.” And in fact, with respect to the previous point, Moore said his organization is taking the steps and building the technologies necessary to do so. One anxiety he shared, however, was that parents from underserved—most often, Latinx—communities are reluctant to share accurate demographic information given the current political climate.

Well, data analysis is often steeped in logical assumptions and inferences. Identifying high-needs areas in the youth soccer landscape needn’t be an exception. A 2007 study found that people who reside within a mile of a park are four times more likely to use it than those living farther away. And decades of federal housing policy has resulted in the demographically homogeneous neighborhoods that exist today.

Therefore, it’s not a massive jump to say: If we know where clubs and teams are playing, and if we know the racial and economic makeup of the populations in those areas, we know which kids are included, and which are excluded.

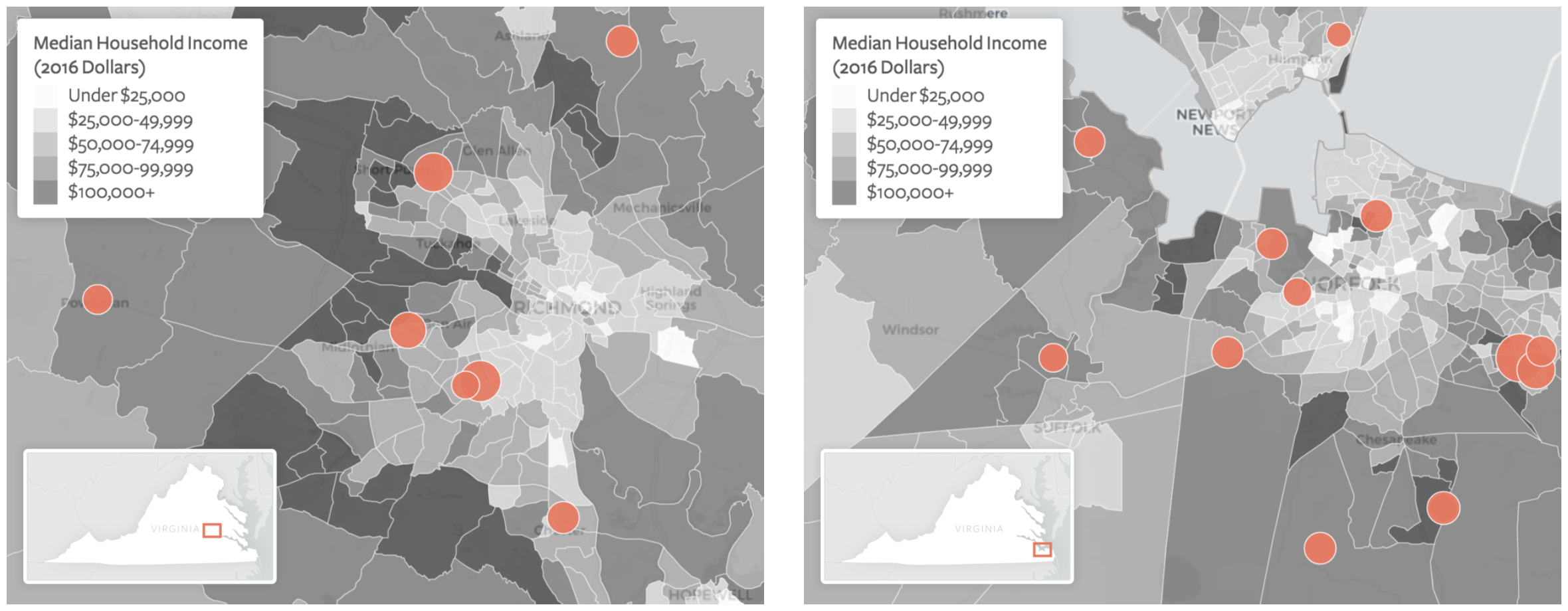

A recent study of competitive youth soccer in Virginia did just that. And the results were in line with long-held assumptions: It’s a wealthy, suburban sport. Below, clubs in the Richmond and Norfolk areas are drawn out toward more well-off neighborhoods.

With the right data made readily available, the federation, state associations, and non-profit groups could properly target resources so that, in Cordeiro’s own words, “kids from urban and rural areas and diverse communities can play, too.”

Shrink the map.

The task force needs to tackle transportation as aggressively as any other issue. According to a national survey of sport for development organizations, transportation is one of the largest barriers to access, with respondents, “referring to long travel times, insufficient means of transportation, and safety in transport as significant concerns.”

And for players who progress through the ranks and into more competitive environments, the demand of travel grows exponentially.

One solution at the grassroots level sees a Maryland club meet children from low-income families after school, provide tutoring services and a healthy snack, and bus them straight to practice. Another solution has seen a Buffalo, N.Y. club and a San Antonio, Texas club carve out safe places to play within urban environments.

Spare time and money are not amenities afforded to parents working multiple part-time jobs. Often, financial aid can be made available, but as one club administrator wrote to me, that aid is turned down because, “they simply cannot get there.” For these families, the map needs to shrink.

Even Cordeiro has acknowledged, “Player development is not a single-lane road.”

Acknowledge the limitations.

It’s been beaten into a pulp: There’s no silver bullet for these issues. Beyond just that, many of these issues will be tackled for the first time. Cordeiro references an “eight-year runway to 2026,” but even that sounds ambitious.

This will take time. And the task force should take the time necessary to get this right.

Along the way, the task force needs to involve all the key players at the grassroots level. They understand the nuances specific to their locality, and they will ultimately be the ones carrying out recommendations. Without them, this proposed task force is useless.

Finally, it should go without saying, don’t lose sight of who matters here. To again borrow from Cordeiro’s remarks, “That love of the game, those hopes for the future—that’s what youth soccer is all about.”